Office Hours with Jon Stokes

If Jon Stokes wasn’t a scientist, he’d be a farmer.

It may seem like a surprising choice for someone who has built a global reputation for using AI to discover new antibiotics, but Stokes is full of surprises. And given that his journey at McMaster University began over 20 years ago mowing the lawn of the then-dean of the Faculty of Health Sciences, it’s a fitting choice.

Often seen donning a trucker hat and a hoodie, his sleeves rolled up showcasing his tattoos, and known for his colourful vocabulary, Stokes, an assistant professor in the Department of Biochemistry & Biomedical Sciences, is reshaping the perception of a scientist. In that vein, he is knocking himself off the proverbial pedestal and aspiring to save lives while helping his hometown cash in on his discoveries.

Growing up in the lab

Stokes, a self-described McMaster “lifer,” grew up in Hamilton, in a house near professor John Kelton. Just before coming to McMaster for his undergraduate degree, Stokes was invited by Kelton to work in his lab in the summer. He worked in Kelton’s lab for three years, after which point he began thinking about pursuing a thesis opportunity. Kelton suggested Stokes reach out to Eric Brown, chair of the Biochemistry department at that time.

“I remember I emailed Eric and I put John Kelton’s name in the subject line… just so Eric would answer. I was just some undergrad, so I 100 per cent name-dropped him,” he laughs. “I didn’t really know what Eric did… I knew he was a fancy-pants chair and that was about it.”

Stokes did a fourth-year thesis in Brown’s lab, finding himself learning about antibiotics. It was only three weeks in the lab before Stokes knew he wanted to stay at McMaster to do a PhD.

“In three weeks, I didn’t comprehend the work. I didn’t understand the significance of it. But I liked being in his lab. Everybody was young and fun and cool – they were focused on their work and dedicated. And I felt like this is a place I want to be. I could see myself coming here every day for five years. And then, before I knew it, I became obsessed with this problem – with antibiotic discovery.”

An ‘imposter’ among the ‘big dogs’

After his PhD, Stokes moved with his wife to Boston for four years, where he pursued a postdoctoral fellowship and began to leverage artificial intelligence methods for antibiotic discovery. But in 2021, Stokes jumped at the chance to return with his family to Hamilton and to work at McMaster. The transition back was a challenge, though, when he found himself a peer among faculty members who were once his teachers.

“That first year was a trip,” he says. “Mike Surette and Gerry Wright were on my doctoral committee. Eric Brown was my supervisor. Now I walk past Gerry and Eric’s labs to go to mine. It’s the weirdest. I walk past my old lab bench and where I used to sit in grad school to get from my office to my students.”

Though it’s been a few years since Stokes returned to McMaster, with many accolades earned in that short time, he still battles imposter syndrome. It’s a tough transition, to now compete for grants with the very people who mentored him along the way.

“I don’t necessarily feel like one of the big dogs,” he says. “I haven’t been doing this that long. But at the same time, I am their peer and I’m hyper-competitive – I want to eat their lunch and I hope they want to eat mine, too. Friendly competition keeps everyone sharp,” he says.

No time for ego

What you won’t learn in conversation with Stokes is that he is a Banting Fellow – a recipient of Canada’s most prestigious postdoctoral award. He will also glaze over the fact that the host institution for his postdoc was The Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard University. He may also shrug when you mention that his innovative work on AI-guided drug discovery was named one of the year’s top discoveries by The New York Times.

He’s unimpressed by his own accomplishments and doesn’t yet feel he’s made a meaningful enough contribution to claim his relevance in the scientific community.

“I can count on one hand how many patients’ lives I’ve saved,” he says, motioning a big, round zero with his hand. “I haven’t done anything that’s truly felt by our communities, we’re still laying the groundwork for inventions that will save patients. I can’t look in the mirror and feel proud because I haven’t done enough yet. No one has left the hospital for home because of something I’ve done – to me, that would be a significant contribution.”

“I work for people who I don’t know yet – the people who I hope will benefit from the discovery of new antibiotics. All the other stuff, awards or recognition, is meaningless. It doesn’t mean one thing – not one little bit.”

Stokes doesn’t sleep much these days, he admits. He’s kept awake not just by the pressure of his own success, but the responsibility he feels to the students in his lab and the taxpayers and donors who fund his work.

“I feel a lot of pressure,” he says. “I lay awake thinking about if I’m enabling my students to do everything that I know they can do; am I maximizing the productivity behind every taxpayer and donor dollar that goes into our research? People give up part of their paycheque so we can do this work, so I feel a responsibility to make sure there’s a really good return.”

Crunching the numbers

For Stokes, the most frustrating part of his work is that antimicrobial resistance (AMR) was under control for nearly half a century but has since surfaced as one of the top global public health threats due to what he says is a lack of political and economic will and investment.

AMR occurs when bacteria and other microbes evolve to withstand the medicines that once killed them, leaving people and animals vulnerable to the infections that they cause and rendering the medicines themselves obsolete.

The human toll of AMR is top of mind for Stokes – 1.5 million people are expected to die from a drug-resistant infection this year – which is more than 4,000 people per day and 170 per hour.

“I know this is a fixable problem and I know roughly how much money and resources we need to do it. I also know the time will come when people and governments will decide the societal toll of this problem is no longer acceptable and that’s when this problem will go away. The only question is when, not if.”

By his calculations, AMR could be under control for the next 100 years if there was a global investment of $20 billion. Stokes says that the G7, which has a combined GDP of $50 trillion, could solve this problem for the next 100 years by allocating a mere 0.04 per cent of that $50 trillion to fighting antimicrobial resistance — a figure so small in this context, Stokes says it could be chalked up as a rounding error.

The issue is that developing new drugs is expensive and time-consuming, Stokes says. It takes 15 years and costs over a billion dollars (USD) for one drug to get to market, and because microbes continue to evolve, any new antibiotics are destined to face eventual resistance – making it unattractive for companies to invest in antibiotic research and development. And so Stokes isn’t waiting for international action on AMR – he’s established a company, Stoked Bio, to quickly mobilize on moving drug candidates discovered in his lab toward commercialization. He’s also working with students as an innovation coach in The Clinic, McMaster’s health innovation hub, and as an instructor in the Heersink School’s Master of Biomedical Innovation program to bridge the gap between technology development and its transfer into local, national, and international biomedical markets.

“The company is really a mechanism to seamlessly move inventions from the lab outside of the academic ivory tower to actual medicines for patients,” he says. “Plus, Hamilton is my home, too – I think it would be really cool if I could make a ton of people here really rich.”

Faculty & Staff, Feature, Office HoursRelated News

News Listing

9 hours ago

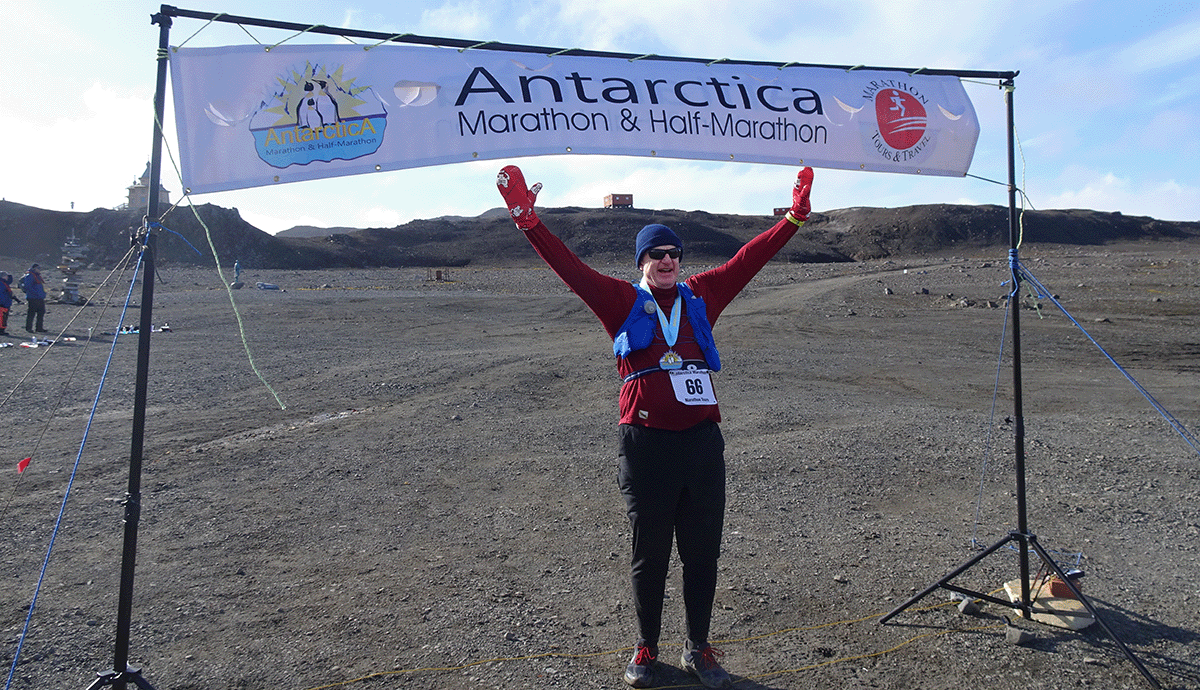

30 marathons, 7 continents: A vice-dean’s running journey across the globe

Faculty & Staff, Feature

3 days ago