Mpox: What this infectious disease physician wants you to know

The World Health Organization recently declared mpox a “public health emergency of international concern” amidst widespread outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of Congo and other parts of Africa.

The declaration comes following the emergence of a new, more dangerous variant, which has since also been reported in Sweden. Experts fear that further spread may soon be on the horizon.

“We are very likely only seeing the tip of the iceberg,” says Zain Chagla, an associate professor in McMaster University’s Department of Medicine and a member of the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research.

While Chagla says that further spread is inevitable, he also notes that the virus’ long incubation period coupled with effective prevention and control strategies could help mitigate mpox’s global impact in the months ahead. Still, he says staying informed is critical, especially if you belong to a high-risk group.

Here, Chagla explains the virus, how it spreads, who is at risk, and how to stay safe from infection.

What is mpox?

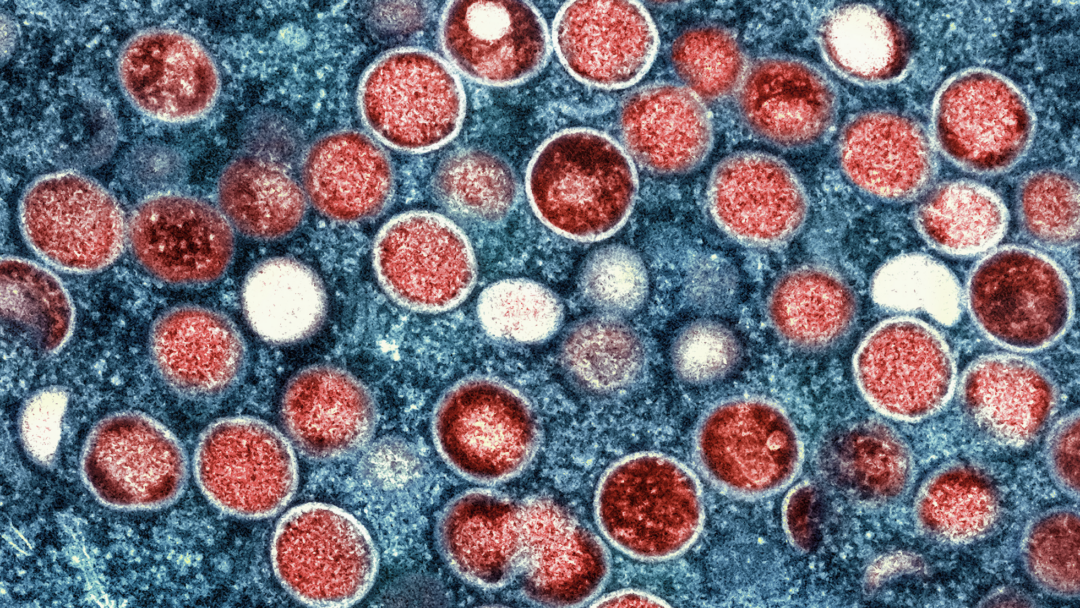

Mpox belongs to the Orthopoxvirus genus in the large family of Poxviruses. The virus that is perhaps most well-known from this group is smallpox, which is an agent that caused significant skin issues for a number of years before it was eventually eradicated by an effective vaccine. Mpox is from the same family, emerging in central Africa. In recent years, it has begun to spread outside of the region, leading to the public health concerns in the news today.

Skin lesions are the trademark symptom of mpox, but what other symptoms should people be aware of and when should they see a doctor?

Mpox can present fever and localized swelling in the lymph nodes, in addition to the typical blisters that the infection is known for. These blisters can be different in size and shape, and can be very localized in minimally infected individuals. There are certainly a number of other skin viruses that can mimic mpox, like herpes simplex, but testing is appropriate even if you only have one or two lesions, especially if you belong to one or more of the risk groups. Anyone who has lesions and fits into a risk group should see their care provider immediately. I recommend calling in advance to ensure mpox testing can be done. If it cannot, you can look to your regional public health website to learn where mpox testing is available.

How is mpox primarily transmitted?

Each particular clade has its own unique epidemiology; however, from a viral standpoint, mpox is primarily transmitted from close contact between people. This can include skin-to-skin contact or sexual activity. The virus can also spread through contact with contaminated objects or environments, and there is likely is some degree of zoonotic transmission in people who live near wildlife or rainforests. Regarding the individual clades, clade 1a seems to spread primarily through close contact and perhaps zoonosis — less so through sexual networks — while clade 1b and clade 2 are much more closely linked to sexual activity.

Who is most at risk of infection and serious outcomes?

Certainly for clade 2 mpox, gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) are at risk — particularly those with multiple sexual contacts and those who do sex trade work. Additionally, healthcare personnel who handle mpox samples and people who travel to rural areas of countries with outbreaks are also at risk. Anyone in any of these risk groups should seek testing if they develop lesions of concern. Of course, as the epidemiology shifts and we start learning more about clades 1a and 1b, the list of at-risk groups may grow or change. In terms of poor health outcomes, the one group that is particularly at risk is people living with HIV. Individuals who live with HIV should strongly consider getting vaccinated for mpox.

What preventative measures can one take, especially if they belong to a risk group?

Safe sexual practice is important — access to barrier-protection, such as condoms, can help keep people safe. As noted, there is also an effective vaccine that is available to those who belong to risk groups. It’s a two-dose vaccine given a month apart — you need both doses for optimal protection. It’s also very important that those who are experiencing lesions isolate until they can see a care provider. As well, it’s important to be cognizant of having good hand hygiene and clean living environments.

What has happened in recent weeks that has escalated the mpox situation to the point of global health emergency?

Mpox has been circulating endemically in Sub-Saharan Africa — particularly in the Democratic Republic of Congo — for quite some time. We had seen a few imported cases in other countries, but the virus had largely been restricted to Sub-Saharan Africa. In 2022, that changed — we saw the emergence of clade 2 mpox that was spreading well outside of the region, particularly amongst men who have sex with men. This clade exited Sub-Saharan Africa and spread — and is still spreading — globally. In fact, we continue to see cases in Canada today. Then, in early-2024, yet another clade — clade 1b — emerged in the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo. This new clade is an offshoot of the mpox that was endemic to Sub-Saharan Africa, which is now referred to as clade 1a. Clade 1b, however, has already been reported in several other African countries, including Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda, and Kenya, where the virus seems to be spreading quite quickly. This new clade is invoking great concern, as it is very clearly not respecting borders. It is also concerning because a number of the countries most affected by this current outbreak have resource and healthcare limitations. We are very likely only seeing the tip of the iceberg in terms of spread.

The Public Health Agency of Sweden recently confirmed a case of 1b mpox — the first known case outside of Africa. Does this jump to Europe signal pandemic potential for mpox?

We can certainly expect that cases are going to show up here and elsewhere. We are a very interlinked global community — people travel in and out of high-risk areas all the time. As well, certain populations that are at risk of contracting mpox are stigmatized, so their ability or willingness to seek healthcare may be limited, which can contribute to further spread. That being said, this is a virus that has a long incubation period — typically five days or more — and so there is some opportunity to intervene before it can spread. Post-exposure vaccination and isolation can both really limit the virus’ ability to spread at a larger rate than has been seen to date. Despite that, broader spread is absolutely possible. It is important to remain vigilant and ensure that we are offering barrier-free care, testing, and education to those who may have been exposed. It’s also critical to reduce stigma, because, as we saw during the mpox vaccination campaign in 2022, marginalized groups within the MSM community were less likely to get immunized, and vaccination is key to containing viruses before they can spread.

Can the eradication of smallpox teach us anything about controlling mpox?

The smallpox eradication campaign was probably one of the most pivotal events in human history. It is the only infectious disease that has ever been eradicated from humankind. Our success in eliminating this virus was due to global collaboration efforts in case and contact management and concerted vaccination campaigns. There was recognition that smallpox could only be eradicated if all countries participated and had access to appropriate resources. In this context, global control efforts could certainly be applied to the mpox situation — if not for total eradication, then certainly for significant mitigation of spread.

Are any of the interventions that worked so well against smallpox viable options for the treatment and prevention of mpox?

The vaccines that we use for mpox were initially developed for smallpox. They are used as a biosecurity measure for those who work with smallpox or Poxviruses in laboratory settings. Those vaccines were used as a control effort against the 2022 mpox outbreak, with significant rates of success. Similarly, tecovirimat — or Tpoxx — is a therapeutic that was developed specifically for smallpox, but can be used to treat mpox as well. This drug also played a key role in controlling the 2022 mpox outbreak.

Dept. Medicine, Education, Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease ResearchRelated News

News Listing

Department of Medicine ➚

Pain to progress: An impactful history of lupus research and care at McMaster

Collaborations & Partnerships, Education, Research

December 20, 2024

December 16, 2024

December 10, 2024