Home

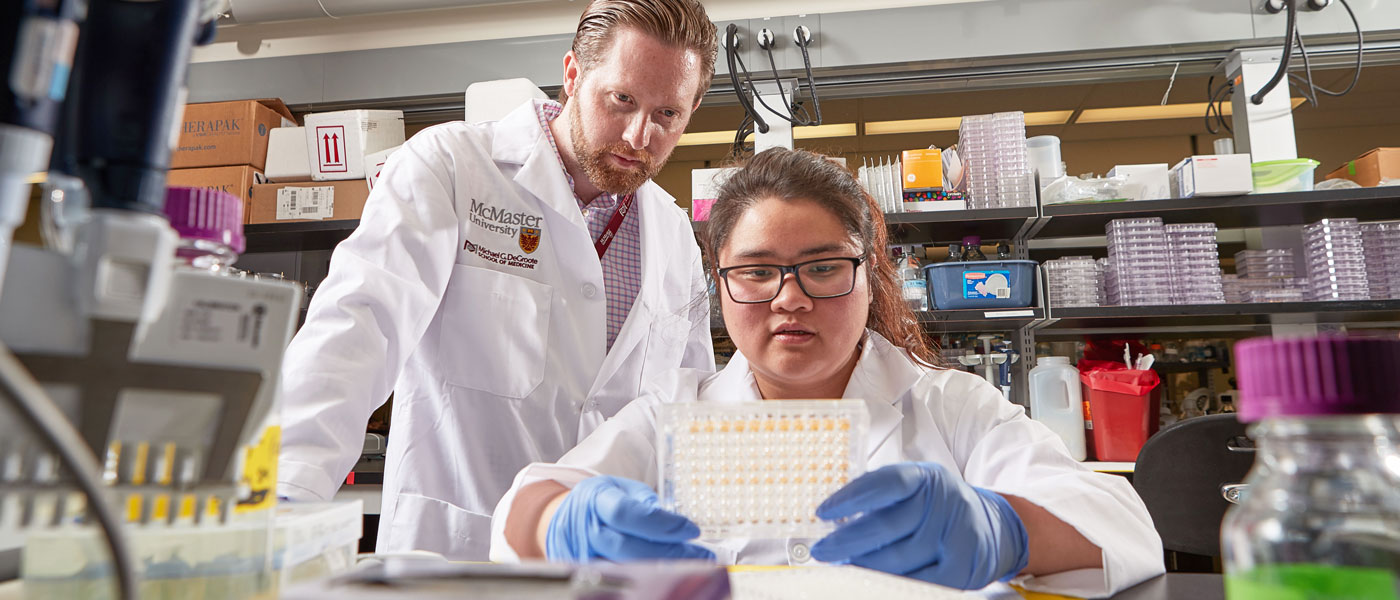

Welcome to the Faculty of Health Sciences

A global leader in health education, research and training, and home to some of the best and brightest minds in the world, the Faculty of Health Sciences at McMaster University is shaping the future of health care in Canada and around the globe.

Latest News

Office Hours with Christian van der Pol

Faculty & Staff

Gordon Guyatt awarded the Henry G. Friesen International Prize in Health Research

Awards & Recognition

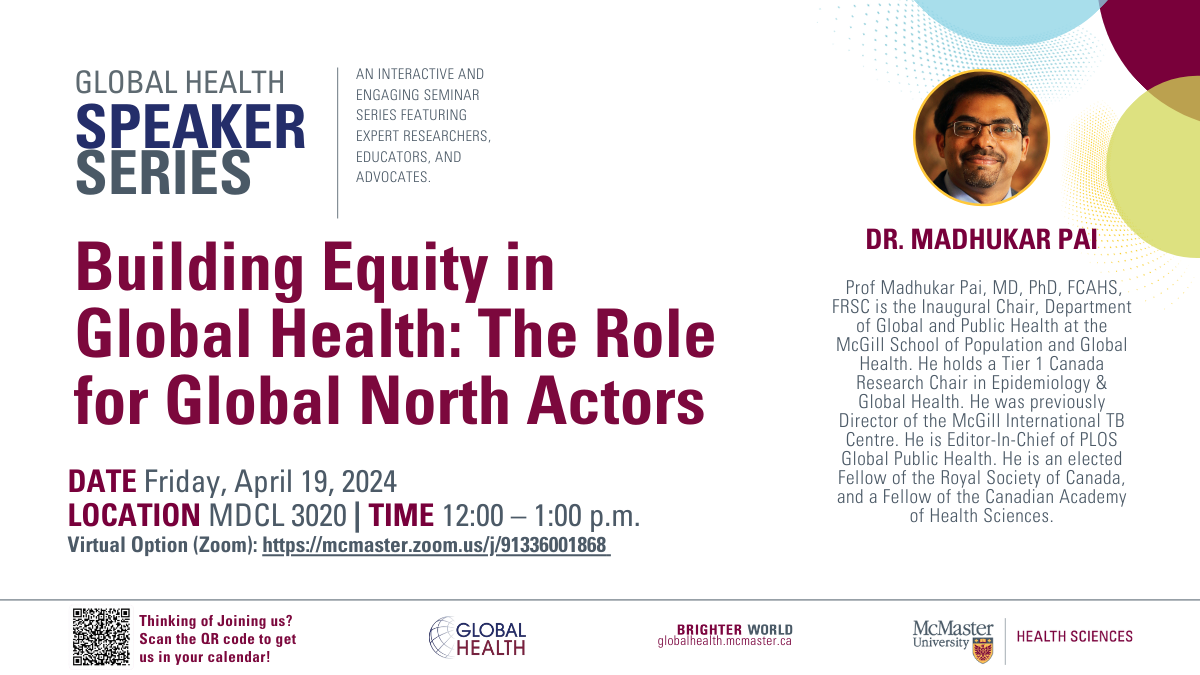

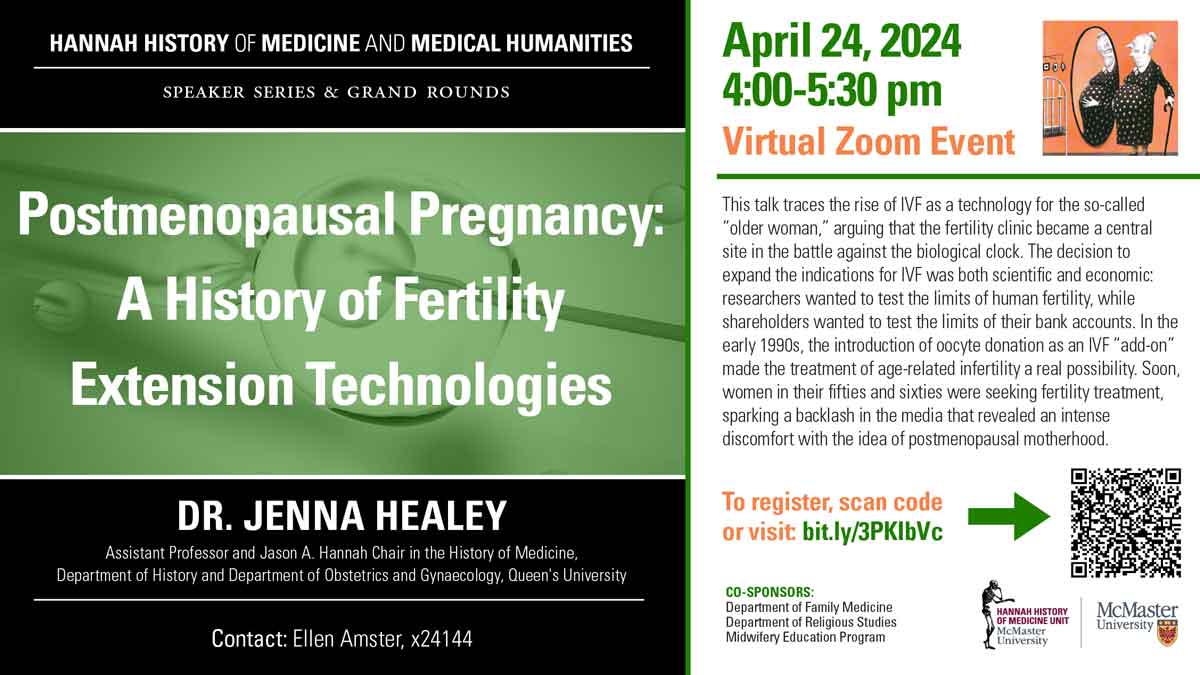

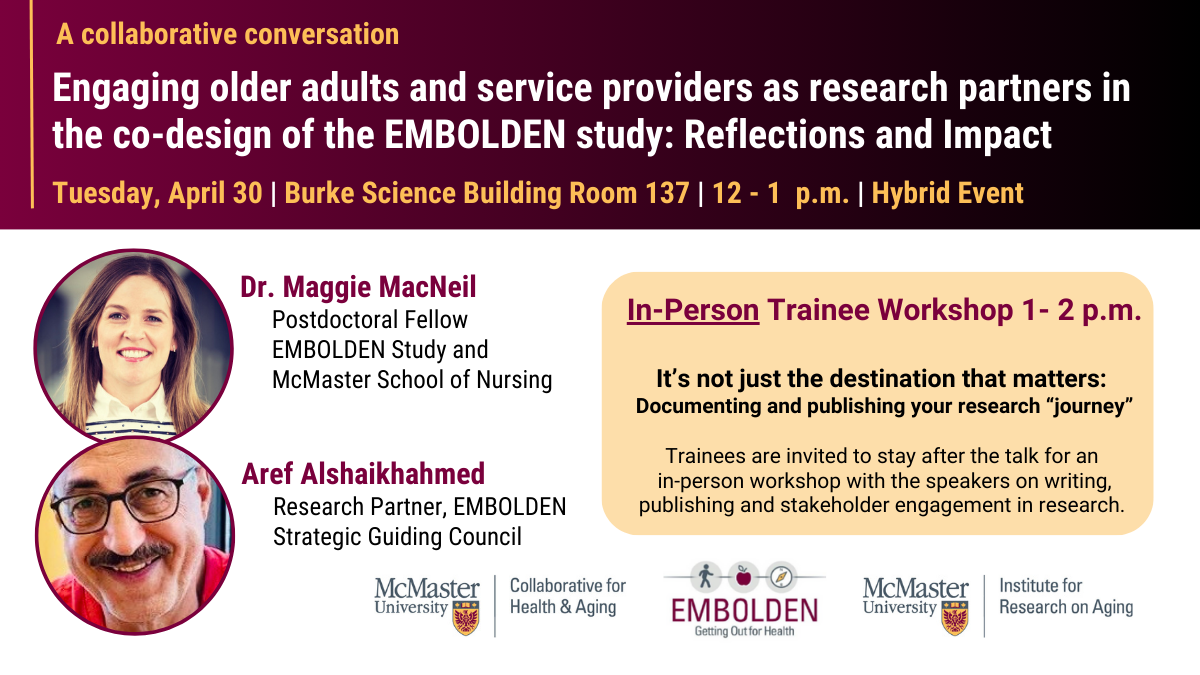

Upcoming Events

McMaster Advanced GRADE Workshop

Workshops